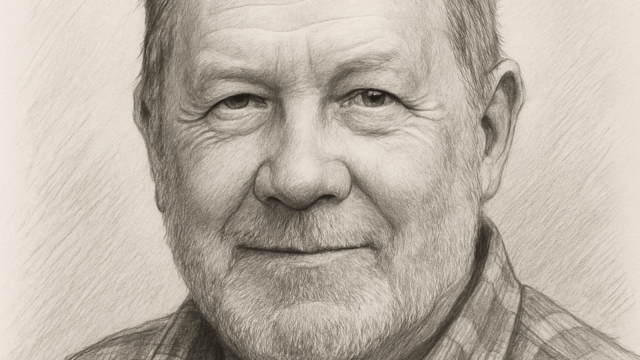

Dr. David Seddon, researcher and former professor of development studies at the University of East Anglia

Dr. David Seddon, researcher and former professor of development studies at the University of East Anglia

Dr. David Seddon, researcher and former professor of development studies at the University of East Anglia, has worked in and written about Nepal for decades. Having first gone to Nepal as a researcher in 1974, he has examined the political economy of Nepal in his work since then. During the Maoist insurgency in the 90s, he forged links with the Maoists and the UML (Unified Marxist-Leninist) party.

In this conversation with The Indian Express, Seddon explains why the ongoing Gen Z protests that forced Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli to resign are unlike past movements, how decades of stagnation and remittance dependency set the stage for this moment, and why Nepal’s experience should serve as a warning to countries “dominated by older men.”

Q. How do you think the current youth-led movement compares with earlier upheavals – Maoist insurgency, the unrest in the 90s, and the push for a democracy?

I think it seems to me to be quite different. We’re in a period where for the last three decades the government of Nepal has rotated really between three older men — the leaders of the three main parties — the Maoist party, the Unified Marxist-Leninist (UML) party, the Nepali Congress. And really, it’s been a period of stagnation and growing corruption.

This is a movement that essentially was triggered by an attempt by the government to close down on social media, which is much used, TikTok and Instagram and so on, by young people. But underlying it is a deep frustration about the way in which politics has stagnated and corruption has grown. So, it’s very much a youth movement and not directly linked to the political parties which is extremely unusual in Nepal.

So it’s much more of a spontaneous movement. It has broken out in a number of cities and has a number of different groups involved. And none of the leaders as far as I know are directly affiliated with the three main parties. So, this does look quite different.

Q. Since Nepal has a young population, has the political system underestimated the volatility of that population?

Definitely, that is the case. One of the major features of Nepal’s political economy over the last three or more decades has been that very large numbers of young people have not found employment or other economic opportunities in Nepal, and have gone abroad and work in the Gulf or in Malaysia or elsewhere. I think that the political classes have tended to expect that any dissident young men would have gone abroad to work. So, they, I think, have underestimated the youth, as in fact is the case in a number of other countries, in Bangladesh, Indonesia, you can name a few. I think that it’s very much run by older men.

Even within the parties, younger people find it very difficult to speak out. Rather like India also, it is a hierarchical system. So younger people…less attention is paid to them than should be. This is an opportunity they have found to rise up and object. I think this is novel; this is new for Nepal.

Q. What lessons do you think the political class in Nepal may be able to learn from this movement, if they were to deal with the current crisis and prevent similar unrest?

I think that it’s a lesson for almost all countries which are on the whole dominated by older men. Everything from the United States where Trump is in his seventies, right across the board, tends to be not exclusively men but older people, and I think they are on the whole ignoring their younger colleagues; using them very much as cadres…as tools. But they ignore this group at their peril. India and Nepal have young populations, and these people need to be integrated into a political process that is fully democratic and not authoritarian and patriarchal.

Given the nature of social media, young people all over the world are aware of what’s happening in Nepal as well as elsewhere. So, I think it’s a message to all leaders of political parties that if you don’t integrate your young cadres and give them opportunities to express themselves in a peaceful political fashion, there is a risk that they will demonstrate and they will just take matters into their own hands.

Q. How do you see this movement that remains outside of the party system? Could it destabilise the federal republic, or push the parties towards reform?

The question is very much open at the moment. A lot of my Nepali friends and colleagues are debating this; what will happen, who will take charge. My guess is that the two alternatives are — either the more conservative establishment forces will intervene to try and calm matters and take things back to normal, or else they will risk this becoming a continuing problem for the status quo. I don’t think that Nepal will fall apart. I don’t think it has been a democracy. It has been a political party system. These demonstrations were not foreseeable. Either establishment figures of a neutral kind will intervene, which I think is most likely. Or, they will fail to correct themselves.

It will take a great deal for the political parties to reform themselves, but maybe this is a wake-up call.

Q. Since these protests are decentralised, does that make them more powerful or more fragile?

Clearly, there is a degree of orchestration. Demonstrations are not just in Kathmandu but in many towns across the country. So, it has been coordinated but it is not structured in the usual way. Now I think that that could mean that it’s more liable to become fragmented – when authorities say you must go back to your homes and be peaceful and you’ve made your point which is what’s being heard now, that they will go home and the movement will disintegrate. That’s one possibility. The other one is it will become more organized, more orchestrated and become a real force, which I think is an interesting possibility, but perhaps the least likely. Well, the third is that it will just fragment and people will stay at home and think they’ve done what they could.

Q. Were the underlying problems that triggered the protests mostly urban?

It affects the whole country in a general sense in that young people are affected and marginalized and, on the whole, find very little employment either in rural areas or urban areas. But it’s definitely an urban phenomenon. I mean all political movements except for organized peasant revolts and the Maoist insurgency is focused in the towns, but it’s not just Kathmandu. It has happened in Pokhara and Birgunj. It’s certainly not just confined to Kathmandu. And that, I think, is quite striking because in Nepal, perhaps unlike many other larger countries, the dominance of Kathmandu demographically and politically is very substantial.

Q. Since Nepal’s economy relies heavily on remittances, has this weakened the state’s accountability towards its citizens?

Nepal has become, increasingly, since the mid-1990s, more and more dependent on remittances. It has meant that a large number of young people are out of the country. The fact that so many young people have been abroad has allowed the older leaders of political parties to not take sufficient account of young people. So, in that way it’s linked.

Q. What about the nature of the political system that came after the Constitution of 2015 may have contributed to the crisis?

There are three key turning points – one was in 1990 when the Jana Andolan broke out and obliged the king to compromise on what had been a monarchical system. But it remained extraordinarily controlled by a very small number of leaders at the top. The Maoists decided in 1996 that far from continuing with a multi-party system, they were obliged to launch a people’s war to create a revolutionary movement. At the end of that, the Maoists had been very successful, politically and militarily, and were able to reinsert themselves into the mainstream of politics and combine with the other political parties to get rid of the monarchy. That’s in 2006-07.

In 2015, the constitution that is now in place was rushed through in the aftermath of the earthquakes in April-May 2015. I think there are many people who are still very unhappy with what the Constitution represents. From my point of view, Nepal has never really established a fully functioning democracy. The parties have operated as vote-catching machines. It’s struggling to find an effective government and system of governance, and that’s partly why there’s such frustration among young people.

If one was being optimistic, anyone between the ages of 16 and 36 would feel encouraged by this (the protests) and press for more far-reaching change, for greater representation.

Source: indianexpress